Energy Consumption Comparison: Python 3.14 vs Python 3.11

Luc Dop, Sabina Grădinariu, Nawmi Nujhat, Vincent van Vliet.

Group 24.

This study explores the energy consumption differences between Python 3.14 and Python 3.11, testing the claim that Python 3.14 has a 30% speed improvement over previous versions. We run the same computational tasks in controlled environments and measure power usage, execution time, and overall efficiency. Our setup includes automation for both Linux and MacOS with system parameters that can be tweaked according to the need, ensuring replicability. Future work will involve the --with-tail-call-interp flag once it is working.

Introduction

As programmers, we use programming languages daily, often forgetting how much impact the chosen language, and sometimes even its version, can have on energy consumption and implicitly on the environment [1]. Python is known to be one of the most used languages, but also, according to previous studies such as [2], it is amongst the least green (energy efficient) due to its interpreted execution and dynamic typing.

With the introduction of Python version 3.14, the documentation states that it utilizes a new type of interpreter that should provide significantly better performance. To be precise, preliminary numbers indicate anywhere from ‘-3% to 30% faster’ Python code [3]. With this performance improvement kept in mind, we have decided to investigate this claim to see how the performance increase impacts the energy consumption.

We started by analyzing Python 3.14 default configuration, without any additional optimizations. The documentation also mentions an experimental feature called the tail call interpreter, which is expected to enhance performance further when enabled. The new tail-call interpretation [4] should not be confused with tail call optimization of Python functions [5].

However, this feature is opt-in, requires specific compiler versions (Clang 19+ on x86-64 and AArch64 architectures), and remains unavailable in the default build. Despite our efforts, we could not enable it, because it is not working yet. Therefore, our current study concentrates on benchmarking Python 3.14’s default interpreter against Python 3.11 to assess energy efficiency under highly demanding tasks.

Methodology

To this end, the idea is to use the prerelease version of the Python 3.14 interpreter and compare the energy consumption for the same code snippet for both the new interpreter as well as an older Python interpreter (3.11.9). This should allow us to see whether the supposed faster speeds of the new interpreter impact energy consumption. To assess the energy consumption we used EnergiBridge as suggested in the lectures [6].

Code Snippet Selection

To make sure that the comparison is a meaningful one, we used computationally intensive code that will stress the CPU. We create multiple snippets that can be seen on Github.

Hardware

For the experiment on Windows we used an ASUS Vivobook with the following specifications:

- Windows 11 home.

- 12th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-12650H 2.30 GHz processor

- 16 GB RAM.

- Brightness level of 30

- Resolution of 1920 x 1200.

- Wifi turned off.

For the experiment on macOS we used a MacBook Air with the following specifications:

- macOS Sonoma 14.6.1

- Apple M3 chip

- 16 GB RAM.

- Full brightness level with auto-adjustment turned off

- Resolution of 2560 x 1664

- Power-saving mode turned off

- Wifi turned off.

Experiment Procedure

Before the experiment begins, we create a list of 30 instances of Python 3.11 and 30 instances of Python 3.14. We then shuffle this list to determine the order in which they get run. To warm up the hardware, we begin the experiment by performing a CPU intensive task for 5 minutes. In our case, that means repeatedly calculating the squares of the numbers in the range [0, 10^6) for the duration of the 5 minutes. After this is done, we go through the previously created list and pick a version of Python to run. We then create two sub-processes, one for Energibridge to measure the energy consumption and one to run a benchmark script on the picked version of Python. The benchmark script generates two 1000 x 1000 matrices, which then get multiplied. After this is done and energy consumption has been saved, we let the process wait for 1 minute. This is to prevent tail energy consumption from the previous run from influencing the measurement in the next run. For the experimentation on macOS, the settings varied slightly in terms of instances, warm up time and parameters in benchmark file. In addition to the 30 instances from each of Python 3.11 and Python 3.14, we also tested an optimized mode by setting the PYTHONOPTIMIZE=2 environment variable. This removed assertions and docstrings, allowing execution with minimal overhead and potentially reducing energy consumption. Although it does not make Python code run significantly faster, it serves as a quick optimization for runtime experiments as of our case. We used a warm up time of 1 minute and the benchmark script generated two 300 x 300 sized matrices for multiplication. Although matrix sizes and warm up time differed between platforms, the focus of our study was the relative energy consumption between Python versions on each OS. Since all Python versions were tested under the same conditions within each OS, the observed trends remain valid.

Replication

The replication package of the experiments can be found in this repository.

Results

Analysis of Results on Windows OS

For the Windows experiment we analyze the ‘PACKAGE_ENERGY (J)’ value generated by Energibridge. This is a cumulative value, where we specifically look at the difference between the value at the start of a run and at the end of a run. To try and normalize the data we perform z-score outlier removal.

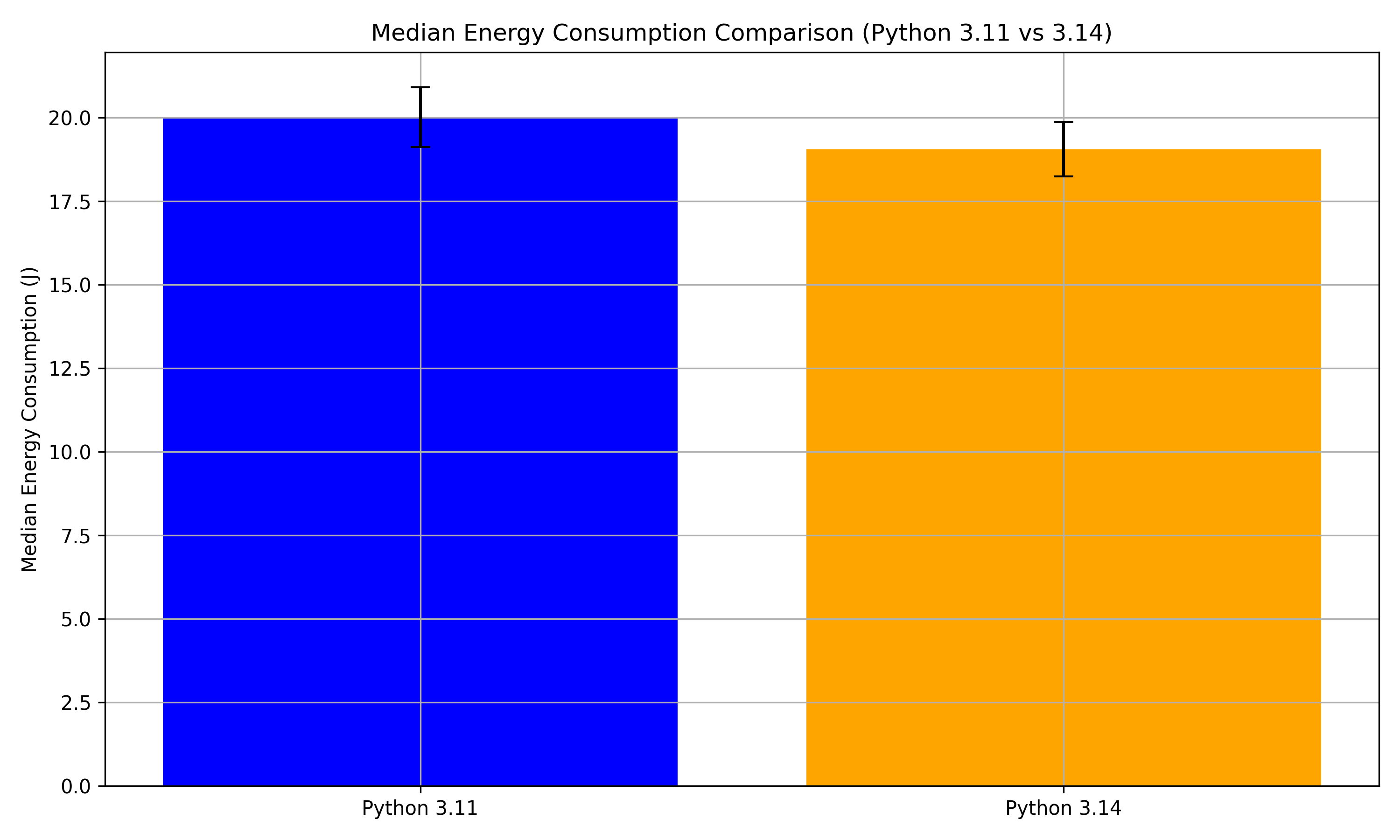

Before analyzing our results, we first check to see if they have a normal distribution. Performing the Shapiro-Wilk test, we see that Python 3.11 has a p-value of 0.091, while Python 3.14 has a p-value of 0.007. This means that while Python 3.11 can be considered normal, Python 3.14 cannot. For this reason, we will look at the median difference between the two sets of results. To graph the difference in median energy consumption between Python 3.11 and Python 3.14, we create a bar plot that uses half of the interquartile range (IQR) as error bars.

Looking at the graph, we see that Python 3.11 has a median energy consumption of 20.01, while Python 3.14 has a slightly lower mean of 19.05. This is a difference of 0.96 J. While this is not a large difference, it could suggest Python 3.14 is slightly more energy efficient. The error bars seem to overlap significantly in both versions however, which could indicate that the difference in median energy consumption between Python 3.11 and 3.14 could be due to normal fluctuations.

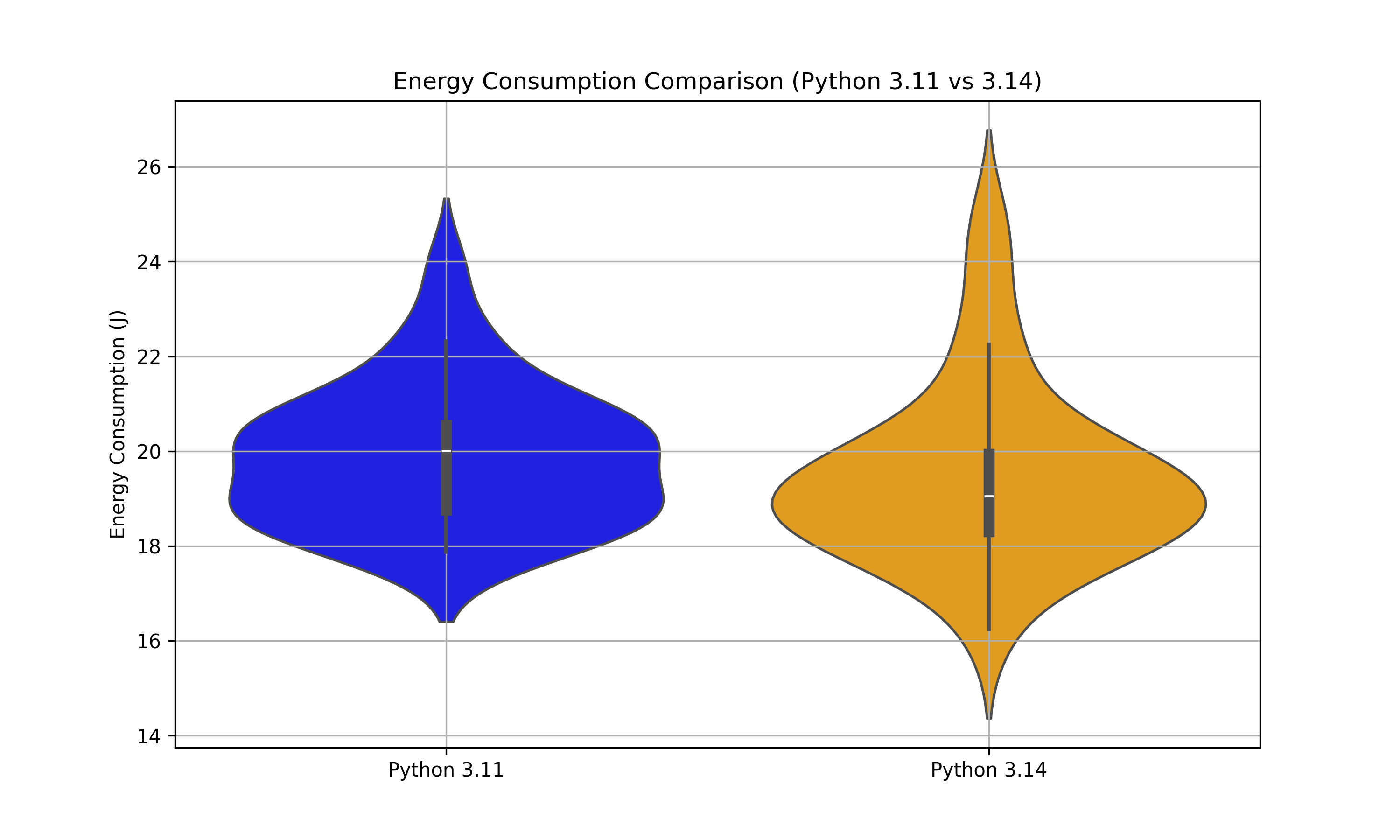

To get more insight into the distribution, spread and shape of the data, we created a Violin+box plot.

Looking at the plot, we see that the results of both versions of python have a relatively wide distribution at the center, showing that for both versions the values are mostly concentrated around 18-20 J. Python 3.14 seems to have broader spread than Python 3.11, with lower outliers extending to ~15 J and higher ones beyond 26 J. This greater number of outliers is consistent with the p-value we found earlier. To check for statistical significance between the two datasets, we use the Mann-Whitney U test, from which we determine a p-score of ~0.15. Since p > 0.05 there is no strong evidence that Python 3.11 and 3.14 have different energy consumption distributions. When calculating the percentage of pairs supporting a conclusion, we see that 61.03% of all possible pairwise comparisons show that Python 3.11 consumes more energy than Python 3.14. This means that in the majority of cases, Python 3.14 is more efficient but not overwhelmingly so. In terms of common language effect size, this is a score of 0.613.

Analysis of Results on macOS

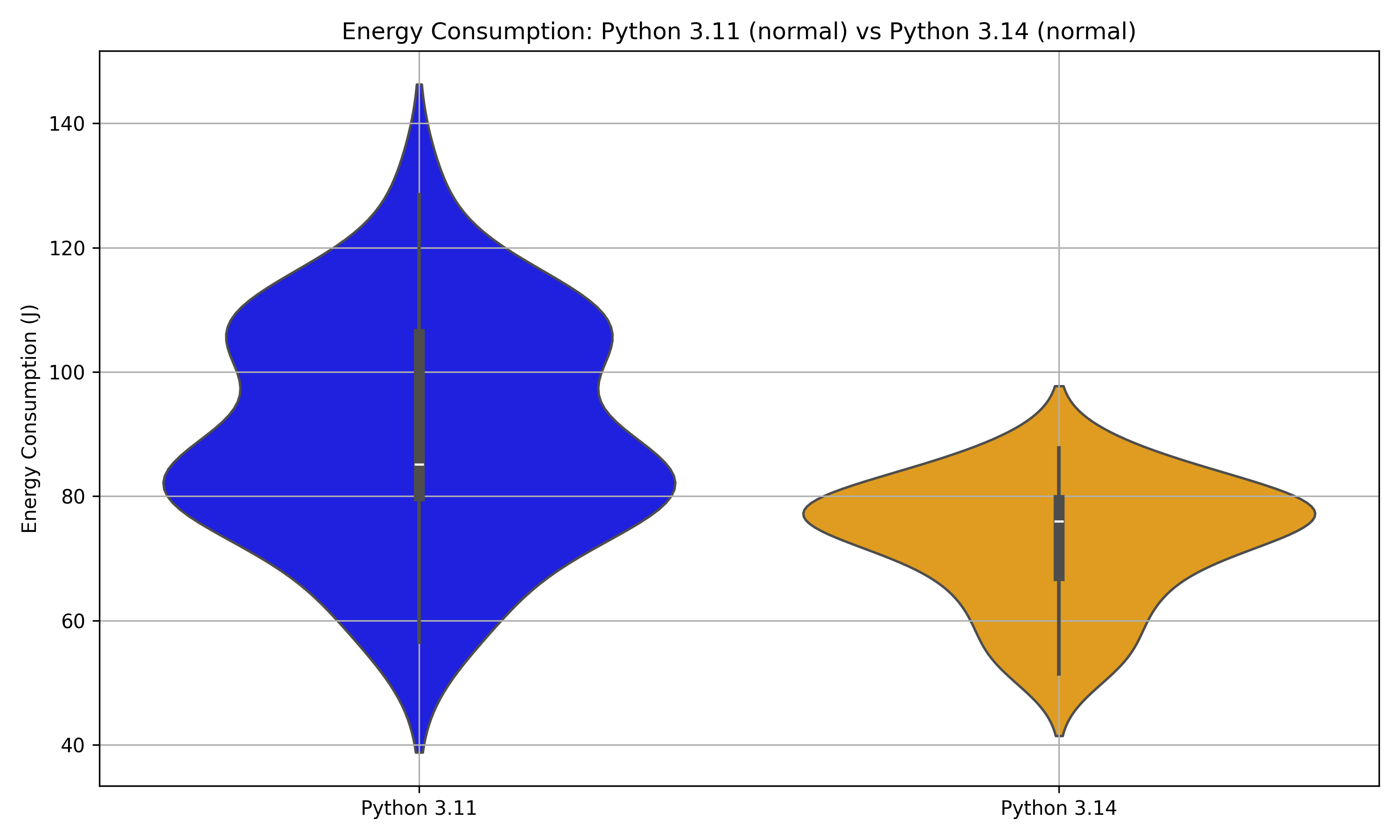

As a preliminary step, we check if the data has a normal distribution for both unoptimized and optimized versions of Python 3.11 and Python 3.14 respectively. Through the Shapiro-Wilk test of the unoptimized versions, we see that Python 3.11 has a p-value of 0.142, while Python 3.14 has a p-value of 0.0655, implying that both of the unoptimized versions of Python 3.11 and Python 3.14 can be considered normal. The observed outcome steers towards the use of Welch’s t-test and comparison of mean energy between the unoptimized versions of Python 3.11 and Python 3.14.

Looking at the graphs, we can see that Python 3.11 has a mean energy consumption of approximately 90J wherease Python 3.14 has the value of approximately 73J, which is approximately 19% lower for Python 3.14. There also exists a statistically significant difference in energy consumption between Python 3.11 and Python 3.14 (unoptimized versions), which is demonstrated by Welch’s t-test. The t-value obtained in this case is around 4.67 and p-value of 0.000000. To get a better insight into the distributions, spread and shape of the data, we created a Violin+box plot.

From the graph, it is visible that both versions display a fairly wide spread of energy consumption. Python 3.11’s distribution stretches from roughly 40J to 140J, with median around 85J. The spread indicates that while some runs remain relatively efficient, others are considerably more energy-consuming. Python 3.14 shows a narrower and lower-centered distribution, spanning approximately 50J to 90J. with median near mid 70sJ. Overall, this distribution sugggests that 3.14 tends to be more consistently efficient, with fewer-high consumption outliers. Because Python 3.14 distribution is shifted downward and is more condensed, it implies that on avaerage, Python 3.14 consumes less energy than Python 3.11. The overlap in violin shapes does mean there can be runs where Python 3.11 performs on par with Python 3.14’s typical range, but such cases are less common. Moreover, a higher value of Cohen’s d (1.211) suggests the difference between two groups to be susbtantially higher. The lower p-value from Welch’s t-test complies with the graphs, showcasing significant difference.

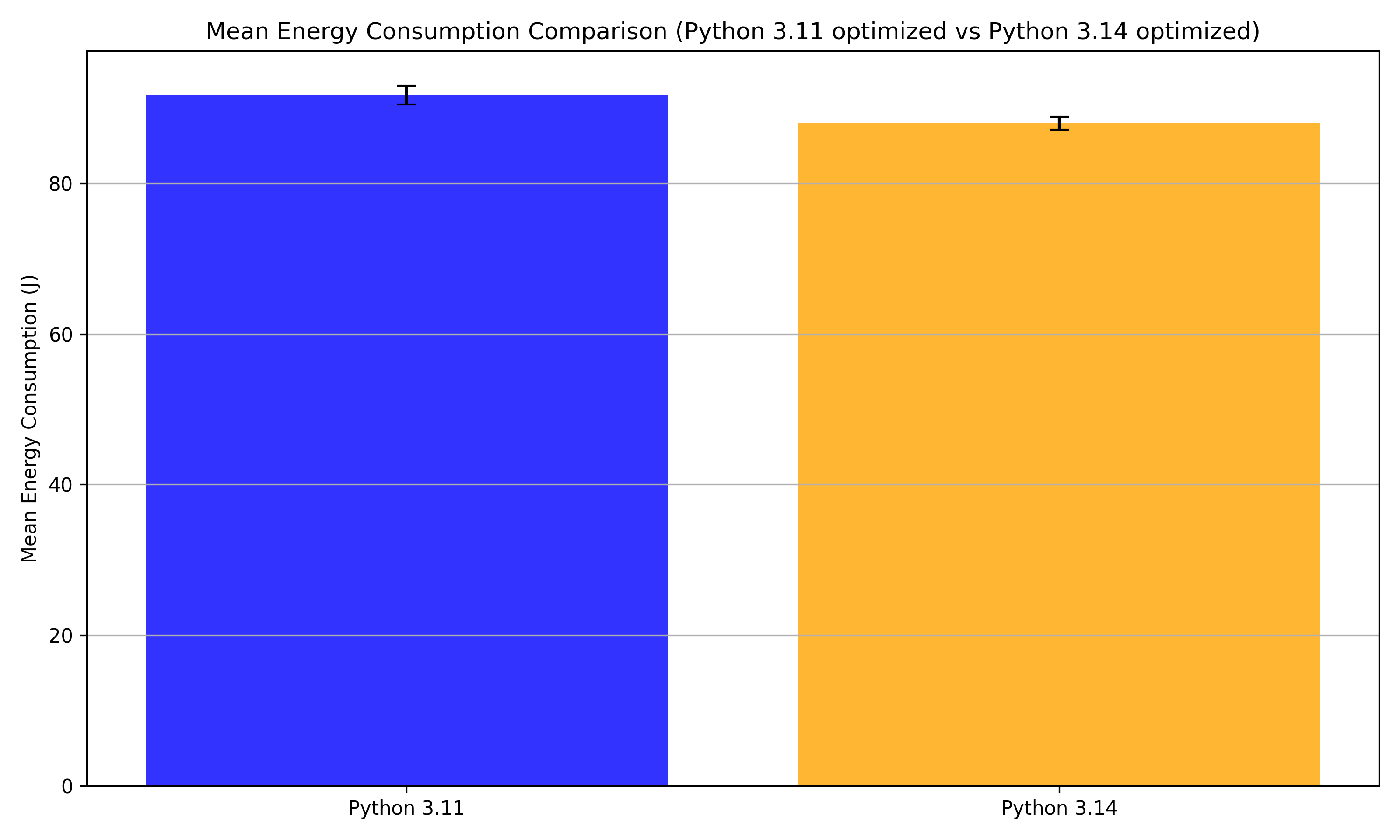

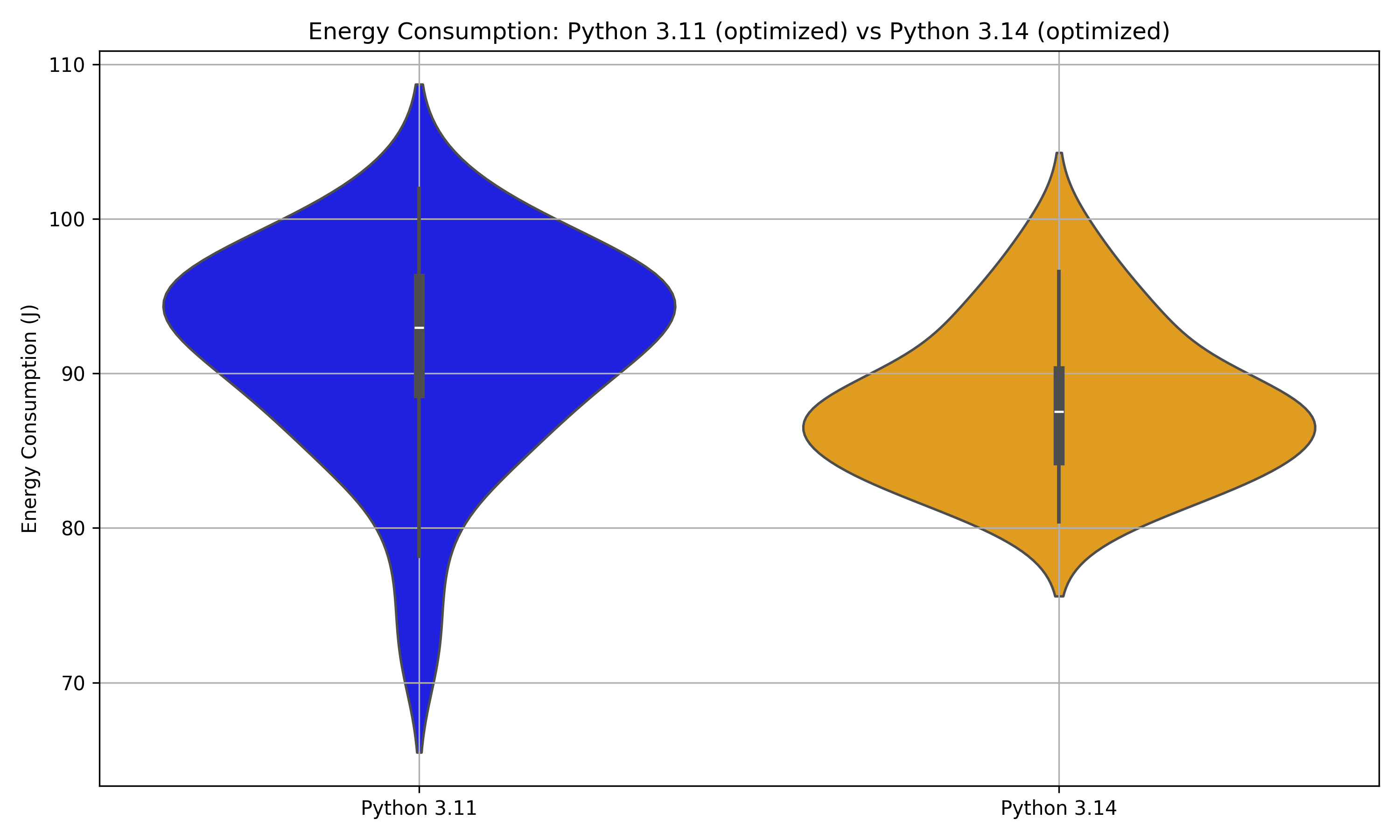

Similarly for the runtime-optimized versions of Python 3.11 and Python 3.14, Shapiro-Wilk tests suggested normally distributed data, so Welch’s t-test and comparisom of mean energy were used.

From the graph, it is seen that the gap between mean energy levels of Python3.11 and Python3.14 is narrowed compared to normal mode (approximately 4% lower for Python 3.14). Welch’s t-test produces t=2.480 and p=0.0165, indicating significant difference in energy consumption even when both interpreters are optimized. A Cohen’s d value of 0.651 indicates moderate difference between the two groups.

For a better insight into the distributions, spread and shape of the data, we created a Violin+box plot.

From the graph, it is visible that the optimized version of Python 3.11 has a broader distribution ranging from 70J to 110J with median at 93J, indicating some variability in energy efficiency. Python 3.14 has a narrower and lower-centered distribution, spanning 80J to 110J with median at 87J. This suggests a greater distribution overlap than unoptimized versions and slightly lower energy consumption. However, Python 3.14 still shows consistent advantage in energy consumption. The higher p-value from Welch’s t-test is consistent with the graphs, implying weak differences, yet significant in comparison to unoptimized versions.

Thus, it can be concluded Python 3.14 is more efficient than Python 3.11 in terms of energy efficiency, with or without the optimizations.

Implications

As previously mentioned, Python’s recent development efforts have been heavily focused on performance improvements. Beyond the optimizations mentioned in Python 3.14, there are other proposals underway such as PEP 703 7, which aims to remove the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) for better multi-threaded performance. These efforts indicate a clear trend: Python is increasingly prioritizing execution speed and efficiency.

However, as the focus shifts towards performance, it is important to also consider energy consumption and sustainability. A common misunderstanding when it comes to sustainable software engineering is the idea that improving the performance of a program reduces the amount of energy used, as this is not necessarily always the case [8]. In some cases, faster execution could mean higher energy consumption per second, but a shorter runtime, as optimizations that improve speed might increase power draw, leading to higher overall consumption 9. These notions should be kept in mind during the further development of Python, as hyperfocusing on performance could lead the language in an unsustainable direction.

An important aspect that is relflected through our study is that computational expense of runtime optimizations can be significantly higher (as seen in Python 3.14) than unoptimized versions. This does not indicate that Python’s optimizations are inefficient, rather they prioritize execution speed over energy-savings for runtime benchmarks. This aligns with the typical behavior in CPU-bound workloads and consolidates our observation that optimizations don’t necessarily mean energy-efficiency.

Another crucial observation was the significant difference between energy consumptions of experiments in different operating systems. For Windows, matrix multiplication of two matrices having dimensions 1000x1000 had significantly lower energy consumption (approximately 75%) in comparison to the matrix multiplication of two matrices with dimensions 300x300 in macOS. The execution time of both of these experiments were 20 seconds and similar conditions were provided. Such discrepancy in values can be attributed to the difference in measurement of energy in the two operating systems. For Windows, only the CPU consumption is measured whereas for macOS, the entire system’s energy is measured, demonstrating a significantly larger value. This trend is consistent in energy consumption of web browsers tested using Energibridge [10].

With regards to our study, we were interested to know whether the claimed performance increase had a similar improvement on energy consumption or not. When comparing Python 3.14 without tail-call-interp with Python 3.11, there was only little difference in energy consumption. Unfortunately, since the pre-release version of Python 3.14 does not give the possibility of testing with the new interpretation feature, we are unable to determine the energy consumption with this feature enabled. For the current pre-release version, in terms of sustainability, our results would suggest that there is not necessarily a reason to switch at this point in time.

Future work

Although Python 3.14 showed no significant performance or energy efficiency gains over Python 3.11 in our tests, future research should revisit this comparison when the tail-call-interpreter becomes functional. With the creation of a replication package, our study ensures that replicating the results on the full version of Python 3.14 with the tail-call-interp feature should be simple when the time comes. To identify potential optimization opportunities in Python 3.14, we could also run demanding I/O scenarios and multi-threading executions.

Conclusion

Our study examined the energy consumption and performance differences between Python 3.14 and Python 3.11. We assess if Python 3.14’s allegedly 30% speed improvement can be seen in energy efficiency. Using EnergiBridge, we measured power usage and execution time across computationally intensive operations. Our results indicate that there is no statistically significant difference in energy consumption or execution time between Python 3.14 (in its default configuration) and Python 3.11.

Given this, we see no convincing motivation to switch from the more stable and well-supported Python 3.11 to Python 3.14 (at this time). The experimental tail call interpreter, which could provide further optimizations, remains non-functional, limiting Python 3.14’s potential benefits.

References

[1] van Kempen, N., Kwon, H., Nguyen, D., Berger, E. (2024). It’s not easy being green: On the energy efficiency of programming languages. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.05460. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/html/2410.05460v1

[2] Pereira, R., Couto, M., Ribeiro, F., Rua, R., Cunha, J., Fernandes, J., Saraiva, J. (2021).

Ranking programming languages by energy efficiency.

Journal of Systems and Software, Volume 174, Article 110889.

Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scico.2021.102609.

[3] Python Software Foundation (2025).

What’s New in Python 3.14?

Available at: https://docs.python.org/3.14/whatsnew/3.14.html.

[4] Python Software Foundation (2025).

Using and Configuring Python 3.14 - Tail Call Interpreter.

Available at: https://docs.python.org/3.14/using/configure.html#cmdoption-with-tail-call-interp.

[5] Wikipedia Contributors (2024).

Tail Call Optimization. Wikipedia.

Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tail_call.

[6] Luis Cruz (2025).

Course on Sustainable Software Engineering.

Lecture materials available at: https://luiscruz.github.io/course_sustainableSE/2025/.

[7] Python Enhancement Proposal (PEP) 703.

Making the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) Optional in CPython.

Available at: https://peps.python.org/pep-0703/.

[8] Yuki, T., & Rajopadhye, S (2014).

Folklore Confirmed: Compiling for Speed = Compiling for Energy.

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Energy Efficient Supercomputing (E2SC ‘17).

Available at: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-09967-5_10.

[9] Anne E. Trefethen, Jeyarajan Thiyagalingam (2013).

Energy-aware software: Challenges, opportunities and strategies.

Journal of Systems and Software, Volume 88, Pages 256-272.

Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocs.2013.01.005.

[10] June Sallou, Luís Cruz, Thomas Durieux (2023).

EnergiBridge: Empowering Software Sustainability through Cross-Platform Energy Measurement.

arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.13897v1.

Available at: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2312.13897.