Energy Efficient Video Streaming: Is It Worth Switching?

Dyon van der Ende, Sam Heslenfeld, Adriaan Pardoel.

In this blog we conducted an experiment to see whether third party video players are more efficient than the default Windows player in the case of video streaming.

Energy Efficient Video Streaming: Is It Worth Switching?

Over the last two decades, the video streaming business has been rapidly growing. It all started back in 2005 when YouTube first launched. Fast-forward to where we are today and over a billion hours of video is watched on the platform every single day1. Streaming services like Netflix and Disney+ have hundreds of millions of subscribers and are making billions of dollars2. Social media platform TikTok even has over a billion active users3. These numbers are huge and they are only getting bigger. Therefore, it is only becoming more important to analyse the environmental impact of this enormous industry.

Before the surge in streaming services that each had their own proprietary video player, most people watched their videos through the standard media player that they had on their computer. Most traditional media players started out with the goal of playing local files and are optimised for this task. But as media playback has shifted to streaming over the years, it might be interesting to see how different media players currently hold up to this shift in media consumption, specifically in the context of energy efficiency, as they may not be optimised for streaming. In this blog we focus on analysing the energy consumption of streaming a video from the perspective of the end-user. We will compare different video players to see whether their implementation has a significant effect on the energy consumption of video playback and whether it might be worth it to switch default players.

For this comparison we chose three popular modern video players: Windows Media Player, VLC, and mpv. Windows Media Player (WMP) has come with almost every Windows computer by default since 19924, while VLC and mpv are cross-platform open-source video players. VLC has hundreds of millions of regular users5, making it the most popular alternative to WMP. It gained much of its popularity due to its ability to play a wide range of different video formats and it boasts an extensive set of features. This is reflected in their developer documentation which states that VLC is “focused on playing everything, and running everywhere6.” mpv on the other hand has a more niche target audience being geared towards tech-savvy people, with flexibility and programmability as its main highlights.

To test whether it is worth changing your default video player, we set up an automated test case that measures the energy consumption of each player while streaming a video. We made sure that each player was updated to its most recent version at the time of conducting the experiment. The versions used are shown in figure 1. The default settings of the players were left intact, as users of media players usually don’t change these.

| Windows Media Player | VLC | mpv |

|---|---|---|

| 12.0 | 3.0.16 | 2022-02-13 |

Figure 1. Used versions of each video player.

The video we streamed in this set-up is called Big Buck Bunny and has a duration of 10 minutes and 34 seconds. The short movie is a project from the Blender Foundation that was released in 20087. The film is made available under a Creative Commons licence and can be downloaded in several file formats8. This makes it a good video to use as a benchmark as others can easily access this video as well. For this experiment we chose the 2D Full HD 30fps version of the video, as this is currently a very common resolution for online video streaming. Other versions that are available include 3D, SD, HD, ultra HD and 60fps.

During our experiment we had two computer systems to our disposal, each with a different configuration, as shown in figure 2. For each device we turned off all unnecessary background tasks and executed a script that automatically ran our test without human interaction required to avoid inconsistencies in measurements between the different video players.

| System 1 | System 2 |

|---|---|

| HP Zbook Studio G4 | Acer A715-74G-792U |

| Intel i7-7700HQ | Intel i7-9750H |

| Windows 10 | Windows 11 |

| 8 GB DDR4 | 16 GB DDR4 |

| NVIDIA Quadro M1200 | NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1050 mobile |

Figure 2. Configurations of available systems.

The first step in the script was to measure the idle power consumption of the device for the duration of the length of the video to serve as a baseline. Then in turn the video players were loaded with the URL to the video and their power consumption was recorded. In between video players we created a small break of 5 seconds to make sure that there was no overlap in recordings.

The power consumption was recorded through Intel’s Power Gadget. This tool records a sample every 100ms and summarises the results of the log. The logs provide individual examination of CPU, GPU and RAM power consumption. A summary of the results is shown in figure 3. For our experiment, the most important measurement available in the collected logs is the Average Processor Power (CPU+GPU) in Watts. We found this measurement to be more appropriate than the Cumulative Processor Power because there were small time differences for measurements of the different video players. These small differences are probably caused by a small difference in startup and closedown time. Moreover, it could be that during one of the measurements buffering of the video took slightly longer. Because the Average Processor Power factors out these time differences, we decided that this measurement would be best for comparison of the different video players. Furhtermore, we used the average power of the idle state to adjust the measurements of the video players, as can be seen in the last row of figure 3. This allows us to compare the video players more precisely by factoring out the power consumption of other processes.

| Idle | WMP | VLC | mpv | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System 1 | System 2 | System 1 | System 2 | System 1 | System 2 | System 1 | System 2 | |||||

| Total Elapsed Time (sec) | 639.937445 | 639.927328 | 639.994426 | 640.042676 | 642.075633 | 635.857897 | 637.511448 | 636.213936 | ||||

| Measured RDTSC Frequency (GHz) | 2.808 | 2.592 | 2.808 | 2.592 | 2.808 | 2.592 | 2.808 | 2.592 | ||||

| Cumulative Processor Energy_0 (Joules) | 2604.661926 | 1860.248718 | 3592.405762 | 6032.364807 | 3279.53949 | 4809.258362 | 3971.585876 | 5792.043945 | ||||

| Cumulative Processor Energy_0 (mWh) | 723.517202 | 516.735755 | 997.890489 | 1675.656891 | 910.983192 | 1335.905101 | 1103.218299 | 1608.901096 | ||||

| Average Processor Power_0 (Watt) | 4.070182 | 2.906969 | 5.613183 | 9.424942 | 5.107715 | 7.563417 | 6.229827 | 9.103925 | ||||

| Cumulative IA Energy_0 (Joules) | 1969.518616 | 1481.190002 | 2234.265076 | 4817.992065 | 2053.58783 | 3762.172119 | 2897.209167 | 4852.072266 | ||||

| Cumulative IA Energy_0 (mWh) | 547.088504 | 411.441667 | 620.629188 | 1338.331129 | 570.441064 | 1045.047811 | 804.780324 | 1347.797852 | ||||

| Average IA Power_0 (Watt) | 3.077674 | 2.314622 | 3.49107 | 7.527611 | 3.198358 | 5.916687 | 4.54456 | 7.626479 | ||||

| Cumulative DRAM Energy_0 (Joules) | 205.860474 | 408.461792 | 447.027222 | 703.646851 | 357.976501 | 575.111511 | 404.840942 | 615.005005 | ||||

| Cumulative DRAM Energy_0 (mWh) | 57.183465 | 113.461609 | 124.174228 | 195.457458 | 99.437917 | 159.753198 | 112.455817 | 170.834724 | ||||

| Average DRAM Power_0 (Watt) | 0.321688 | 0.638294 | 0.698486 | 1.099375 | 0.55753 | 0.904465 | 0.635033 | 0.966664 | ||||

| Cumulative GT Energy_0 (Joules) | 2.828918 | 19.678162 | 384.089417 | 338.007935 | 284.672791 | 202.779175 | 200.077454 | 111.52417 | ||||

| Cumulative GT Energy_0 (mWh) | 0.785811 | 5.466156 | 106.691505 | 93.891093 | 79.075775 | 56.327549 | 55.57707 | 30.978936 | ||||

| Average GT Power_0 (Watt) | 0.004421 | 0.030751 | 0.600145 | 0.528102 | 0.443363 | 0.318906 | 0.313841 | 0.175294 | ||||

| Idle-adjusted Power (Watt) | 0 | 0 | 1.543001 | 6.517973 | 1.037533 | 4.656448 | 2.159645 | 6.196956 |

Figure 3. Results.

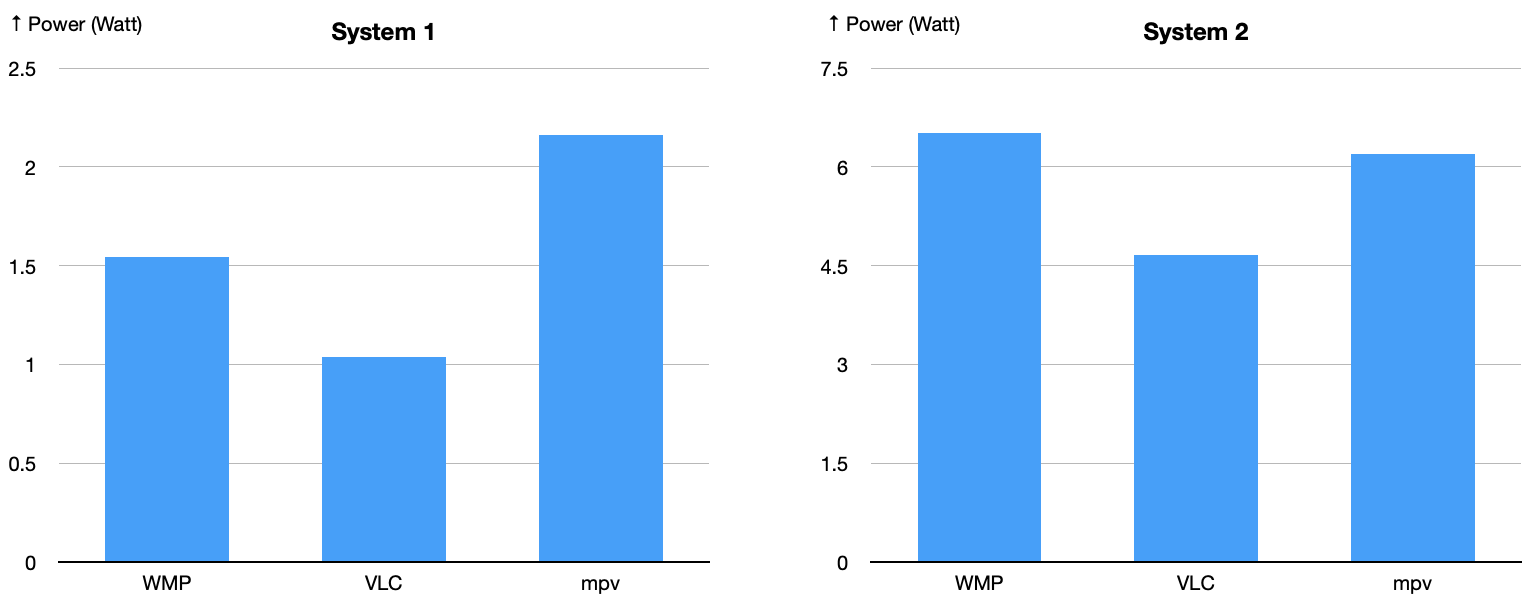

We visualised the idle-adjusted power in figure 4 to compare the most important results more easily. From this figure, it can be concluded that on both systems VLC is significantly more energy efficient than both WMP and mpv. In addition, the power consumptions of WMP and mpv seem to be much closer to each other.

Figure 4. Bar charts of average power consumption adjusted by idle power.

Figure 4. Bar charts of average power consumption adjusted by idle power.

From the results we see that on System 1 VLC is 33% more efficient than WMP and on System 2 it’s 29%, so we can conclude that installing a third party video player (e.g. VLC) can indeed significantly reduce power consumption for video playback, with about 31%. Just think about what this means in practice: if you can normally watch 2 movies with your standard media player on a single charge, you could watch almost a whole additional movie simply by using VLC. However, we also observe that by definition not every third party video player is more efficient. If we look at the mpv, we see that it performs similar or worse than VLC. This is probably because mpv is built with a different use case and end-user in mind: its main focus is its programmability and they might sacrifice efficiency to achieve that, hardware acceleration is for example not enabled by default.

So what makes VLC so efficient compared to other video players? This is probably because it’s a very mature open-source project that’s really focused around usability: it plays everything, is available on every platform, and is completely free. Despite its wide range of features, it’s been around for so long that there’s been a lot of time put into optimising it in every possible way, including its power efficiency. In contrast, WMP is developed internally at Microsoft and hadn’t been updated since 20094, yet still came with Windows by default up until Windows 109. It should be noted, however, that on February 15, 2022 Microsoft released a new version for Windows 114. We could not easily include this in our experiment because not both available systems are running Windows 11 and documentation of the new Media Player is still scarce, so it was unclear if we could control its playback through a command-line interface for automation of the experiment. The fact that it took Microsoft 13 years to update their video player also raises another important point: to stay energy-efficient, software should be updated more frequently.

Although the results give us useful insight in the energy consumption of the three video players, there are some side notes and remarks that should be made regarding the conducted experiment. First of all, it is important to note that the experiment has only been carried out once on both systems. Therefore, the results might not be very reliable and consistent. In addition, the specifications of both systems are different, which could be an explanation for the difference in results between both systems. In idle state, System 2 consumed less energy than System 1, while during the video streaming, System 2 consumed considerably more energy than System 1 for all video players. Even though this difference most likely originates from the fact that the systems that have been used contain different specifications in terms of hardware, it is hard to determine where this difference exactly comes from.

Another limitation of the experiment is that only a single video and format has been tested. While Full HD is still the default resolution, Ultra HD is getting more and more common as the screen resolution of phones and monitors increases. To get a more complete comparison between the different video players, it might be beneficial to also consider other videos, sizes and formats in any future experiments.

Analysing which video player is most efficient gave us insight into potential energy savings that could be gained by making more people switch to a more efficient implementation. We think that analysis of online video players could also bring us new opportunities for energy savings, the impacts of which could be huge given the vast amount of video streamed through online platforms such as Netflix and Disney+. However, analysis of these platforms is slightly more difficult than the video players we consider in our experiment. This is mostly due to three different factors. Firstly, automating the experiment (making it better reproducible) is harder for these online platforms. The video players that we chose for the experiment all come with a command-line interface, making it easy to control them in the experiment. Secondly, to compare energy consumption we need to keep other factors in the experiment constant, including the video that is played. This would not be possible with different online streaming services, as they can only offer the content that they have the rights to. Thirdly, streaming services often use web apps, making the browser choice another variable.

In conclusion we can say that changing the default video player player on your pc could have a significant impact on the power consumption of the device. This is not only more sustainable but also a quality-of-life improvement as this be the difference between watching 2 or 3 movies on a single charge. The result of WMP also shows us that it is important to ship a device with a good default player. Many people do not take the effort to install a third party application, let alone investigate the power consumption of their software. The scale on which WMP is used means that an improvement in energy efficiency could eventually save a lot of energy.

-

https://blog.youtube/press/ ↩

-

https://www.businessofapps.com/data/video-streaming-app-market/ ↩

-

https://www.businessofapps.com/data/tik-tok-statistics/ ↩

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Media_Player_(Windows) ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

https://www.videolan.org/press/videolan-20.html ↩

-

https://code.videolan.org/videolan/vlc ↩

-

https://web.archive.org/web/20080703212311/http://peach.blender.org/index.php/the-release ↩

-

http://bbb3d.renderfarming.net/download.html ↩

-

https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/windows-media-player-12-e8f84f54-cd64-865c-2e83-1d8ec121b5b8 ↩